Today we have a guest post by Saga Hillborn, a historical fiction writer. Her new novel, ‘Princess of Thorns’ follows the story of Cecily Plantagenet, daughter of Edward IV and sister to Elizabeth of York.

Saga Hillborn has very kindly contributed a post about two people who play a big role in Cecily’s story – Richard III and Anne Neville.

Her novel, ‘Princess of Thorns’ will be released on 1st March 2021.

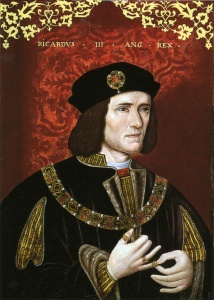

Richard III is obviously one of western history’s most controversial figures. His relationship to his wife Anne Neville is still being both romanticised and portrayed in a negative light painting him as having taken advantage of her. In my upcoming historical novel Princess of Thorns, both Richard and Anne feature as characters; in this guest post that Helene was kind enough to let me write, I will take a closer look at their marriage.

After Edward IV had taken the throne, he placed his much younger brothers George and Richard in the household of his cousin the Earl of Warwick. Richard, who was roughly nine years old, likely met five-year-old Anne Neville for the first time at Middleham Castle. Although they would have undergone entirely different educations, it is reasonable to assume that Anne and Richard were often in one another’s company, as were the other young nobles who grew up at Middleham. It is possible that the Earl of Warwick was already planning his daughters’ eventual marriages to the King’s brothers at this point. Hence, Anne and Richard would have become accustomed to the idea.

In 1465, perhaps slightly later, Richard left Warwick’s household and spent more time at his brother Edward’s court. When Warwick and George, Duke of Clarence, rebelled for a second time in 1470, Richard fled with the King into exile in Flanders. Meanwhile, Anne was married off to the Lancastrian Edward of Westminster. What either she or Richard felt about this match is of course not recorded, but suffice to say that Edward of Westminster was a stranger and an enemy who was described by an ambassador as talking of nothing but cutting off heads.

Richard returned with his brother, and the Yorkist dynasty was restored to power after the battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury in 1471. At this point, Richard’s position was better than ever after he had proven his allegiance and competence—while Anne’s position was dire. Her father and husband had both been killed, and she risked being labeled as a traitor. It is here that we get the image of Richard swooping in either to rescue or to take advantage of his childhood friend.

The Neville inheritance was absolutely massive, including a great deal of land as well as strategic and prestigious castles. The Earl of Warwick had obtained it through his wife, though, who was still living. Their two daughters, Isabel and Anne, were her heirs, and whoever married them would control their share of the inheritance. Isabel was already married to George, Duke of Clarence, while Anne was a widow. Now, both Richard and George scrambled to claim Anne’s share. If she remained without a husband and living under George’s roof, George would control her wealth. If she married Richard, he would. What Anne herself thought is a mystery, but I personally believe that she preferred the idea of becoming Duchess of Gloucester over the prospect of essentially living as a secluded nun. I might add to this that George was notoriously unpleasant and fickle, while Richard was known to be chivalric and loyal. It goes without saying that this is an extremely oversimplified description.

George and Richard argued over the inheritance to the extent that the King’s own lawyers were astonished at the number of arguments they could come up with. Richard had begun courting Anne, which led to George allegedly disguising her as a kitchen maid in Isabel’s London household. The tale of how Richard found Anne and took her with him to sanctuary at St. Martin’s le Grand has become a heart-warming passage in several novels. Whether said tale is one hundred percent true is debatable.

In the end, King Edward helped settle the dispute between his brothers; this involved declaring the Countess of Warwick legally dead to make the inheritance available. Richard gave up the largest chunk of lands and estates as well as the earldoms of Warwick and Salisbury, surrendering to George. Thus, he actually did not gain as much by marrying Anne as popular culture would have it seem. We should keep in mind when looking at their relationship that although Anne was still an heiress, Richard fought long and hard to make her his bride despite George taking the lion’s share of the ‘bounty’. What I think that he gained above all was the support of the north, where the Nevilles had held sway. Anne, on the other hand, obtained security and the title of a royal duchess. They were married in the spring of 1472, when Anne was about to turn sixteen and Richard was nineteen. Seen through a 15th century lens, the age gap was close to non-existent.

The Duke and Duchess of Gloucester only had one child who survived infancy: a son called Edward of Middleham. It is possible that Anne miscarried several times, but like her sister and mother, she could simply have lacked the genetic advantages of the Woodville women when it came to childbearing. Throughout the 1470s, Richard and Anne largely remained in the north, building their good reputation in York. Richard would have been absent for extended periods of time when the King required his services—such as on the military campaign in France 1475–but this was not unusual for a man of his rank. What is remarkable is that he appears to have stayed faithful to his wife, unlike his older brothers in their marriages. He did have two illegitimate children, Kathryn and John, but they were almost certainly conceived before 1471. The most probable reason for Richard’s behaviour is that he was a staunch moralist and very pious, but love could have played a part.

I will not go into the details of Richard’s so-called usurpation of the throne since that would require its own post, but I want to mention the question of Anne’s role in it. Outwardly, she was the perfectly submissive, invisible wife. However, she had considerable influence behind closed doors or rather in the bedchamber, as did many wives. Did she want to become Queen? Did she oppose her husband’s actions? We do not and never will know.

In April 1484, Edward of Middleham died aged around ten. Richard and Anne—then King and Queen of England—were reported to have gone half-mad with grief over the loss of their only child and dynastic hope. Edward’s death was not only a tragedy but a political crisis. Anne was soon twenty-eight years old and appeared unlikely to become pregnant again, while Richard needed an heir more than ever before to secure his precarious position. This eventually led to speculation about him wanting to get rid of his wife; however, he did nothing to encourage these rumours. During the Christmas celebrations at Westminster that same year, a fatal mistake was committed. Elizabeth of York, the eldest daughter of Edward IV, appeared in a dress identical to that of Anne Neville. The likeliest explanation is that Richard wanted to show the court that Elizabeth was reconciled to his side, part of his family as his niece, rather than Henry Tudor’s betrothed. The plan backfired spectacularly. French sources, who were eager to cause disruption in England, and Lancastrian supporters began spreading the rumour that King Richard intended to abandon his spouse in favour of Elizabeth. This was the best ammunition they could have hoped for. We can only imagine what Richard, Anne, and Elizabeth all felt.

It is unclear when Anne first became sick with tuberculosis (known as consumption in the 15th century) and it cannot even be confirmed that she did not suffer from some other disease. By the early spring of 1485, though, she was confined to her chamber, and Richard’s physicians forbade him to visit her in the event that he caught the same illness, giving rise to the saying that he ‘shunned her bed’. In the meantime, people continuously spoke of his impending marriage to his niece, which he denied. The only ‘evidence’ for the supposed marriage plans is a note summarized in a letter by historian George Buck. Neither Buck’s letter nor the note survive, and its supposed contents can be interpreted in several ways.

Anne Neville passed away during a solar eclipse on the 16th of March 1485. At the time, some chose to view the eclipse as a sign of her husband’s sins. She was buried nine days later in Westminster Abbey, while new rumours began circulating that Richard had poisoned his wife. He made a public declaration on the 30th of March saying that he was grieving for Anne and had never intended to wed his niece, issuing orders to arrest all who repeated the slander.

To summarise, the marriage between Richard III and Anne Neville was the result of turbulent events and a scorching dispute but encompassed a decade of presumably peaceful companionship, before finally ending in scandal and tragedy. It is impossible to tell to what extent their match was strategic and to what extent it was romantic, but one thing is clear: they were a power couple.

One thought on “The Marriage of Richard III and Anne Neville”